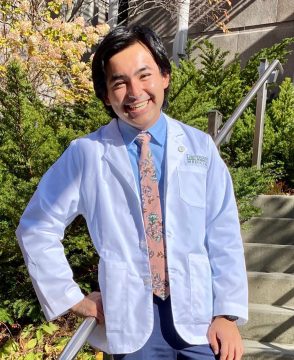

In his medical student grand rounds presentation, Understanding Care Experiences Amongst Immigrant and Refugee Clients in a Ryan White Funded HIV Clinic: Insights to Improve Culturally Competent Care, fourth-year Geisel School of Medicine student Sirey Zhang ’24 (D ’20) emphasized the importance of life stories in caring for immigrants and refugees with HIV.

The yearlong study led by Richard Zuckerman, MD, an associate professor of medicine who leads Geisel’s preclinical infectious disease course, assessed whether the needs of a growing number of immigrant and refugee patients with HIV in Dartmouth Health Ryan White HIV clinics in Bedford, Nashua, and Lebanon, NH were being met and whether aspects of their care could be improved. The Ryan White care program supports clinics providing care and support to low-income individuals in racial and ethnic minority communities.

Recruited by Zuckerman, Zhang was a perfect fit for the study—he studied medical anthropology as a Dartmouth undergraduate where his research and scholarly interests focused on understanding healthcare experiences in the context of the socio-economic, cultural, and political conditions that manifested in structural inequities.

Patients who agreed to having a medical student take part in their care met with Zhang. From July 2022 through August 2023, he interviewed 18 patients and four caregivers—10 patients agreed to audio-recorded interviews and eight shared their stories informally. Interpretation services were available when needed. Zhang also spent 42 hours observing clinical team meetings and direct patient care.

Though Zhang acknowledges it is statistically difficult to show their stories are significant, he maintains they are because individual stories are true and meaningful.

Here’s what he learned.

Patients mostly felt supported, but with a few caveats.

“The patients I talked with have been in the U.S. from a few months to decades—some were documented, some were not, and some were relocated through a refugee program,” he says. “As I got to know them better, we started talking about issues not directly related to their care but that were a big part of their lives. It became clear to me their life stories mattered.

“Through their stories, I found three factors across the clinics that shaped the care they received—clinical, community, and bureaucratic.”

Clinical factors that augment the experience for immigrant and refugee patients, Zhang says, describe a perceived power dynamic, whether people feel insecure about their illness, or belittled, and found “that was never the case in our clinics.”

Historically, the staff “did a terrific job of building empowerment—when patients arrived nobody commented on their illness. But over the past few years, a challenge arose,” Zhang says, “a turnover in healthcare workers due to many factors, including burnout. Because of this, some patients felt it difficult to open-up to new providers.

“Immigrant communities in the Upper Valley and other areas in NH are small and close-knit, and people rely heavily on these close relationships for support,” Zhang explains. “In the clinic, the social effects of staff turnover engendered fear among some patients about sharing something important in their life with a stranger, which became an impediment.”

Zhang also talked about the importance of community. “Given that immigrant communities are small and people rely on their close-knit community for support, there was a fear that having their diagnosis of HIV shared would cause them to lose their support system, so many people adopted ‘double lives,’ hiding medications when their community members came over for significant holidays, for example, or turning away in-person interpreters who they did not know out of fear that there were only had a few degrees of separation. This, I felt, was the most important factor that impacted their care experiences surrounding HIV.”

And lastly, the bureaucratic factors that include undocumented immigrants. “As an immigrant, it's hard to ask for help,” a patient explained, “and it’s even harder when you are undocumented, because you feel that you don't deserve it, even if you feel respected. Embarrassed to share about my lack of documents, I went almost two years without medications … an up-front conversation would have been helpful when I first started."

Another mentioned financial insecurity, “It was so difficult getting papers that allowed me to get adequate insurance here, and I am very worried about how I will pay for healthcare once I obtain a job and my insurance expires. I want to work but I do not want to lose healthcare.”

Zhang notes this is a common dilemma, “They want to work, but by getting a job they would lose their insurance, leaving them to choose one over the other.”

The clinics did a good job of welcoming all patients into a safe, non-judgmental space—but some still felt a bit ashamed asking for care because they were undocumented and, Zhang says, believed they deserved less.

According to one provider: “We had a formerly steady client who dropped out of contact, and it took a year for them to get back in touch—they were afraid of getting picked up by immigration enforcement. We are fortunate that they haven’t been.”

Zhang appreciates the immigrant and refugee patients with whom he talked and says they deserve “a special thanks for sharing their stories because they are the heart of this work.”

Based on the study’s findings, next steps include continuing to engage the clinical team in discussion; identifying avenues to intervene on community and bureaucratic factors, for example, during new intake, establish a sense of support and security in terms of documentation status, offer mechanisms for the clinical team to involve family/community members; and establish a mechanism to monitor and report outcomes.

“What drove me to medicine is understanding how these inequities from political and economic forces shape individual care,” Zhang says. “That’s something I hope people keep in their mind as they interact with individuals throughout their careers in medicine.

“This is important to me and frames how I want to carry myself into the future.”

This research was made possible by the generous support of the Dartmouth Health Ryan White clinics' staff and the Infectious Disease Society of America's G.E.R.M. program for funding participant compensation and research expenses.