In late 2018, when the Hybrid Master of Public Health (MPH) class of 2019 at The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice gathered to discuss selecting their class gift—they were excited about their prospects.

“Class gifts at The Dartmouth Institute are legacies meant to benefit future classes,” says Reid Plimpton, MPH ’19, who served as class gift chair on the student advisory council. “We did really well with our fundraising efforts, which had included holding a silent auction, and were able to say, ‘Alright, well, we get to think big here.’”

A survey conducted earlier by the council with the class had shown that most of the students favored leaving some sort of physical gift rather than an endowment or scholarship.

“So, we got back together and asked, ‘What would be a great sort of symbol of true public health kind of work?’” says Jordan Fraser, MPH ’19, who as president of the student advisory council worked closely with Plimpton on the project. “Someone suggested creating a replica of the John Snow Pump, which we’d learned about in our epidemiology class. We thought the idea was a total home run.”

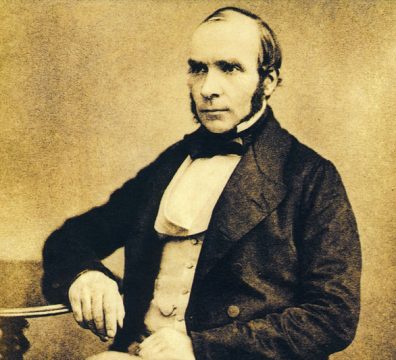

When he heard about the class’s gift idea, Craig Westling, DrPH, MPH, MS, executive director of education for The Dartmouth Institute, enthusiastically supported it. “The John Snow story is a really important one for the history of public health,” says Westling. “He is considered by many to be the founder of epidemiology—someone who showed that collecting and analyzing data at a population level can lead to specific interventions that have an immediate impact on the health of individuals and the collective whole.”

In 1854, Dr. John Snow, an obstetrician interested in many aspects of medical science, traced the source of a deadly Cholera epidemic to the Broad Street Water Pump in London. Snow had long-believed that Cholera was transmitted through local drinking water (first producing research on the topic in 1849)—as opposed to the popular belief at the time that the disease was spread through the air.

Through painstaking research, and a fair bit of persistence, Snow created a detailed map showing where cases of cholera occurred in London’s West End and was able to convince the local city council to disable the water pump by removing its handle. This reduced Cholera transmission dramatically and saved many lives.

The MPH class would face a number of challenges, some foreseen and some unforeseen, in bringing their ambitious project to completion. “Getting the pump made was the hardest part for sure, requiring key contributions from people both within and outside the Geisel School of Medicine,” says Plimpton.

For starters, the 2019 class officers—including Plimpton, Fraser, Dawn Zeiger, Lamar Polk, and Joe Belisle—did online research and corresponded with the John Snow Society in London to obtain life-size dimensions of the pump, which had been reinstated at Soho Square, London in 2018. They then worked with two New England-based undergraduate students and Green Foundry in Eliot, Maine to develop the project.

“Henri Bizindavyi, an architecture student at the University of Maine at Augusta, heard about our plan from one of his professors and offered to help us,” Plimpton recalls. “He created an electronic 3D model using a sketch image that we found online.”

From there, Seamus Hall, a studio arts (architecture) and economics major at Dartmouth College, added segments to the model that allowed it to be printed. “He developed a 3D printing of the top portion of the model and used PVC piping to create the lower stem,” explains Plimpton. “Once the stem was attached, Seamus added a finishing layer and painted the 3D model black (as requested) so that we could show the top part of the pump on class day.”

From there, Seamus Hall, a studio arts (architecture) and economics major at Dartmouth College, added segments to the model that allowed it to be printed. “He developed a 3D printing of the top portion of the model and used PVC piping to create the lower stem,” explains Plimpton. “Once the stem was attached, Seamus added a finishing layer and painted the 3D model black (as requested) so that we could show the top part of the pump on class day.”

Still, more work needed to be done to finish the project—including having the final pump replica cast at the foundry, and having it fitted with a sturdy granite base and mounted with a commemorative plaque. “We also had to figure out where it should go,” says Fraser, who worked with Geisel Dean Duane Compton and the medical school’s facilities department to secure an appropriate location.

“We decided on the connecting foyer between Kellogg Auditorium and Anonymous Hall, a space that was due to undergo some renovations at the time,” recalls Fraser. “We finally got everything done and ready to go and then COVID hit. The combination of the pandemic and the delayed construction really set us back—I think the pump was temporarily housed in our classroom space on the seventh floor of Vail for more than two years.”

Today, the John Snow Pump replica sits in its final resting spot in the foyer for all to enjoy. “When I walk by and I see people stopping to look at this life-sized sculpture and read the plaque, I’m grateful that we have it,” says Westling. “There’s more awareness now of the pump itself, of epidemiology, and of our MPH program’s connection to the broader medical school community. I think that promotes interdisciplinary thinking about our most vexing problems, which is excellent.”