For Release: January 16, 2009

Contact: dms.communications@dartmouth.edu, 603-650-1492

Dartmouth Researchers Identify Potential Cancer Target

From left: Sam Bakhoum, M.D.-Ph.D. candidate; SarahThompson, Ph.D. candidate; and Duane Compton

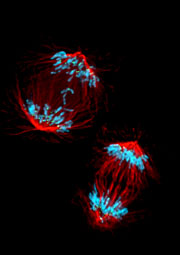

Two anaphase spindles from the control (lower) and Kif2b-depleted (upper) cells. The chromosomes are in blue, and the upper spindle contains two lagging chromosomes—shown in the middle.

Hanover, N.H.—Dartmouth Medical School biochemists have found two proteins that work in concert to ensure proper chromosome segregation during cell division. Their study, published in the January issue of Nature Cell Biology, may offer clues to treating cancer tumors that shuffle chromosomes.

Solid cancer tumors commonly lose the ability to separate their chromosomes accurately, a process called chromosomal instability. These tumor cells nonetheless keep growing and have a poor prognosis.

"We show that the function of two proteins, called Kif2b and MCAK, is to correct improper attachments during cell division to prevent the mis-segregation of chromosomes" said Dr. Duane Compton, professor of biochemistry at Dartmouth Medical School. "The two proteins share the workload: Kif2b acts early in cell division and MCAK acts later. This cooperation underlines the importance of proper chromosome segregation for the healthy life of all cells."

Compton, who led the research, is also director of the cancer mechanisms research program at Norris Cotton Cancer Center at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center. He explained that the discovery follows a finding his team reported in the Journal of Cell Biology last year pinpointing chromosomal instability. They showed that the main cause was that chromosomes make errors in hitching to the spindle apparatus—the fiber-like structures that orient and separate chromosomes in dividing cells.

"These improper attachments occur normally during cell division in all cells, but in the tumor cells, the improper attachments fail to get corrected and cells attempt to divide with persistent improper attachments," said Compton.

We discovered how to make the tumor cells faithfully segregate their chromosomes every time the cell divides.

—Dr. Duane Compton

The current study shows the two proteins complete their job by regulating the attachment between the chromosomes and the spindle apparatus. Based on these results, the team also determined that increasing quantities of either Kif2b or MCAK in tumor cells restored nearly normal accuracy of chromosome segregation.

"We discovered how to make the tumor cells faithfully segregate their chromosomes every time the cell divides," said Compton. "Chromosomal instability has been studied for over a decade in tumor cells; this is the first time anyone has suppressed it in tumor cells indicating a strong causal relationship between correction of improper attachments of chromosomes to the spindle apparatus and chromosomal instability. These results give us insight into the overall mechanisms of cell division in tumor cells compared to normal cells, and we may be able to exploit that, leading to new therapeutic strategies or treatments that might prevent tumor progression."

Compton and his team will now work to directly test the contribution of chromosomal instability to tumor development.

Co-authors on the paper include: Samuel Bakhoum, Sarah Thompson, graduate students, and Amity Manning, a former grad student, all with the Department of Biochemistry at Dartmouth Medical School and the Norris Cotton Cancer Center. The research is supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health.

-DMS-