Promoting Equity or Hallucination?

Today’s choice of article for the alcove is inspired by the Editorial that just came out in Academic Medicine setting a policy for AI tools like ChatGPT: “The use of artificial intelligence (AI) tools must be disclosed at the time of submission…AI tools may not be listed or designated as authors. Authors are accountable for the quality and integrity of their scholarly work.” They didn’t come down 100% against AI, but they are making clear that they are not sentient enough to be “accountable” for authorship (at least yet–read some speculative fiction for some future possibilities!).

This editorial got me wondering about what’s out there so far on tools like ChatGPT in health professions education and, amazingly, there is already a review on it (Sallam, 2023–see below for full citation). Unamazingly, this early review is published by the Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI), which meets the criteria for a predatory publisher (one who publishes almost anything and makes money off of it). So, let’s take the findings with a grain of salt–thinking of it as having a learner or research assistant do an initial search for us, but knowing we’ll have to do a more rigorous search and potentially some additional research later.

First, some interesting history: AI as something scientists study (according to our “grain of salt” article) originated at Dartmouth in the summer of 1956 (see then Assistant Professor John McCarthy’s proposal along with three other scholars here). In true speculative fiction fashion, they thought that “every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can in principle be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it” (McCarthy et al., 2006, p. 12).

Fast forward to 2023 and we have generative pre-trained transformer (GPT) architecture, which “utilizes a neural network to process natural language, thus generating responses based on the context of the input text” (Sallam, p. 2). Sallam set out to probe the (minimal!) literature to determine the potential benefits and risks of this technology. He included in his search any published research, whether peer reviewed or not, but excluded non-academic articles from things like newspapers and magazines. This is an example of just one of many choice points you have when you do a literature review (something you should definitely bring one of our awesome librarians in on sooner rather than later if you’re looking to publish).

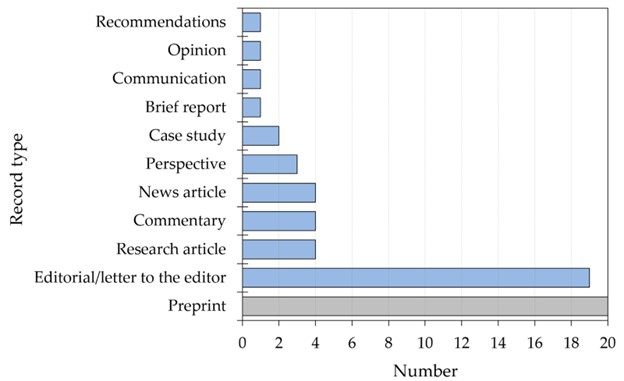

Sallam ended up with a corpus of 60 articles that he extracted data from. (A shameless plug: you don’t need interviews to do qualitative research–you can use many qualitative analytic techniques on articles–it’s a cool form of data extraction! Reach out to me if this intrigues you…) Also distinctly unamazing, very few were peer reviewed research articles:

Yet these preprints and editorials give us a starting point for thinking about ChatGPT in education and research. Some of the benefits are:

- The accessibility that its ability to generate or improve rough drafts gives to non-English speaking scholars.

- The analytic capabilities when you have reams of textual data.

- The educational shortcuts like having it generate a first draft of a clinical vignette or offering suggestions for how to have difficult conversations with patients

Yet, as the Academic Medicine editors reference, there are some major risks, too, including:

- Ethical issues like bias (especially given that it is all based on publicly available data, so it’s ONLY open access scholarship, for instance) and plagiarism.

- Transparency issues–you know how Reviewer 2 always wants to know more about your methods? If you use ChatGPT, you might not be able to tell them.

- Legal issues like copyright (ChatGPT doesn’t generate a lovely list of works cited)

- Hallucination

The last one is my favorite–at first I thought it meant you might have some kind of psychadelic experience if you use ChatGPT and was very curious. But it actually means that Chat GPT can “hallucinate” supposed facts that seem super reasonable but actually are untrue.

So the lessons here as I see them are:

- It’s worth considering how ChatGPT might enable you or others to make scholarship more accessible and less time consuming.

- Be very, VERY careful if you do choose to use ChatGPT because it may not be ethical or legal and it can even make you hallucinate.

- This is a new and growing area of research so maybe there’s some work you might want to do on how it relates to your field!

I’d love to hear your thoughts on either this content or these methods and if any of this has gotten you interested in starting a project, reach out for research support any time!

These reflections are based on a 2023 article from Healthcare (available freely online): Sallam M. ChatGPT utility in healthcare education, research, and practice: systematic review on the promising perspectives and valid concerns. In Healthcare 2023 Mar 19 (Vol. 11, No. 6, p. 887). MDPI.

Other References

Li T, Higgins JPT, Deeks JJ (editors). Chapter 5: Collecting data. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.3 (updated February 2022). Cochrane, 2022.

McCarthy J, Minsky ML, Rochester N, Shannon CE. A proposal for the Dartmouth summer research project on artificial intelligence, August 31, 1955. AI magazine. 2006 Dec 15;27(4):12-.