Match Day is an important day in the life of graduating medical students—it’s when they discover where they will be spending their residency. This story (parts 1 and 2) features seven students on the cusp of their professional careers.

|

Part 1: |

Part 2:

|

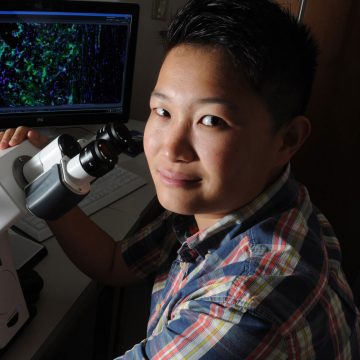

Yike Jiang ’19: Leap of Faith

Back in 2015 as an MD-PhD student, Yike Jiang ’19, received the Pricilla Schaefer Award for her work investigating how our immune system's response to the ubiquitous herpes simplex virus can lead to blindness, and how it can be prevented. The award recognizes promising young investigators and commemorates Schaffer’s contributions to herpes virology and her dedication to mentoring young virologists.

During those early days of graduate research with David Leib, professor and chair of microbiology and immunology, Jiang says she was a bit naïve and unsure of what she was doing at first, but receiving the award changed that.

“That award boosted my confidence as to who I was, what I wanted to be, and how to be successful in research, which I’ve learned is a combination of luck, trial and error, and persistence,” she says. “In lab, when something doesn’t work, you do it again and again—it feels like insanity—but that boost in confidence gave me the creative energy to take risks in thinking differently about problems and to try something wildly crazy. And that leap of faith led to success.”

With Lieb’s mentorship and encouragement to pursue her own work, Jiang took another look at a microscopy experiment that was not working. “The negative control was not negative, and objectively, it means that the experiment was a failure. But what it told me was there were existing antibodies in the nervous system that previously had not been appreciated,” she says. “That was a game-changer. The dogma was in question. The immune system and the brain are supposed to be separated, but right in front of me was evidence that refuted the dogma—and I took this finding in a very different direction from the expertise in the lab; I took it to neonatology.”

She found that these antibodies are passed on from a mother to her baby, protecting them from neurological infection that can damage the brain or cause death. “I didn’t have a lot of time to step into the lab during my fourth year, but the project continued after I left. Chaya Patel, the grad student who took over this project, found that antibodies produced by maternal vaccinations can prevent mortality and behavior changes from neonatal herpes. Having been part of her training, I feel particularly proud to see her blossom and succeed as a researcher.”

This research experience led Jiang to pediatrics. After commencement, she’s off to Texas Children’s Hospital and Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, TX. “They have this special research track for pediatrics, so not only will I be doing my residency, I’ll also be doing clinical and basic science research at the same time,” she says. “I’m excited for what’s ahead. I’ve learned a lot at Geisel, but I’m ready for my next great adventure.”

Adrianna Stanley ’19: Predicting the Future

Adrianna Stanley ’19, is a bit of a nomad.

She has traveled the world pursing her longtime interests in global health and tropical medicine—spending a summer in the Peruvian tropical basin researching malaria in Latin America as a National Benjamin H. Keene Travel fellow; addressing health inequities in Central America, acquiring a range of skills that allowed her to make a deeper impact in San Jose, Costa Rica, where she provided primary healthcare services to uninsured Nicaraguan immigrants in one of the city’s poorest neighborhoods; as a Geisel Global Health Scholar, traveling to Guatemala as part of a medical team providing cleft lip and cleft palate surgeries.

She spent the past year living in England pursuing a master’s degree in Control of Infectious Diseases at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, which is comparable to a master’s degree of public health in the U.S. but focused on infectious diseases and transmissible illnesses. She studied vector-borne diseases from mosquitos and other bugs that transmit disease, focusing on quantitative analysis of disease transmission dynamics—looking at disease incidence in a specific geographic area then mathematically modeling interventions to see their effect on predictive disease outcomes.

An early fascination with the evolution of disease producing bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites drives her interest and her frustration with their persistence in a world with so many advances in medicine and technology.

Stanley’s family is originally from San Jose, Costa Rica, and for her tropical medicine is also about health equity—she wants to make sure those who are most underserved in the global community have access to quality healthcare and are no longer burdened by preventable disease. In an earlier story written about Stanley, she said, “Tropical medicine is the face of my mother who lives everyday with cysticercosis. It is the sound of my three-year-old Costa Rican cousin crying from the misery of dengue fever, and it is a place where patients with Chagas, Leishmaniasis, and Leprosy should no longer be judged because of their diagnosis.”

Following Match Day, Stanley headed to an eight-week global health clinical elective in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania where she is immersed in an urban setting at the country’s primary referral hospital that includes three weeks of internal medicine and four weeks of pediatrics along with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and tuberculosis (TB) research projects. “I’m working in a hospital to see how they deliver care—seeing prevalent diseases in patients with TB, HIV, malaria, and dengue that I’d previously worked with mathematically,” she explains.

Though most of these are preventable diseases, Stanley says she won’t be making a difference during her two-month stay. “I’m not here to make a difference. I’m here to learn how they practice medicine. I want to learn alongside Tanzanian medical students and understand how their healthcare system works. But in the future, I hope to use these continuing global health experiences to inform how I’ll practice global medicine because these are health inequities that no one should have to live with.”

Learning about the transition of HIV care in the adolescent population aligns with Stanley’s goal of becoming board certified in both internal medicine and pediatrics. She says, “We see this problem a lot when pediatric patients with chronic illnesses transition into adult care—they drop off the map and this is particularly true with HIV care in Tanzania where the age of transition is around 14.”

During her time in Dar es Salaam, she is continuing research on the impact of the Dar-901 vaccination on TB among adolescents in Tanzania—a project managed by Ford von Reyn, MD, a professor of medicine at Geisel, and Lisa Adams MED ’90, associate dean for global health at Geisel—which she began in 2018 as a medical scholar of the Infectious Disease Society of America Foundation.

“Using mathematical modeling for TB vaccine interventions, we can map immunization efforts onto known epidemiologic and demographic factors of Dar es Salaam to inform our predictions about how well we think the vaccine might prevent infection or reduce incidence of TB in this region,” she explains.

“Mathematical modeling is a skill that allows me to practice global health wherever I’m living,” she says. “It’s an impactful tool you can use remotely to make mathematical predictions of where disease is headed and based on these modeling predictors, public health departments can scale-up, implement, or change interventions—this brings together epidemiology, public health, and clinical medicine, which is why I like it.”

After returning to Geisel for commencement, Stanley is off to UCLA Medical Center for a medicine-pediatrics residency—a growing field that gives physicians an opportunity to see patients of all ages in both the clinical and hospital setting.

“Medicine-pediatrics is a great way to combine primary care and hospital-based care—it’s the best of both worlds because you can provide outpatient and inpatient care for both children and adults,” she says.

Ever the world traveler, Stanley ultimately sees herself returning to London as an infectious disease physician and global health clinician in academic medicine.

Alex Tarabochia ’19: Longitudinal Relationships

Third- and fourth-year clinical rotations can be challenging—every eight weeks Geisel students find themselves in a new clinical environment integrating with a new clinical team. A situation that some find overwhelming, others find rewarding.

Alex Tarabochia ’19 found it rewarding.

“My car became a walk-in closet during my away rotations—sometimes it was awesome, others not so much,” he recalls. “Though it was difficult, it all worked out in the end.”

No stranger to the dynamics of creating community harmony and the effort it takes to forge strong ties, Tarabochia is comfortable in situations many may consider stressful.

He completed a one-year AmeriCorps service term in Jacksonville, Florida where he served as a case manager for the male partners of women receiving pre- and postnatal care in a high-risk clinic. The aim was to reduce the alarmingly high rate of infant mortality in an area of the city challenged by a stark color and poverty divide.

The expectant parents shared intimate details of their daily lives with him—Tarabochia’s gentle, trusting nature inspires confidence and the divulsion of secrets. He values these relationships and says they are of critical importance to him as a physician who wants to build longitudinal relationships with his patients.

During an obstetrics and gynecology rotation, he thought that specialty would provide the patient interaction he wanted. “I loved the taking care of the patients and I really loved childbirth—that was my favorite thing—being there to birth babies,” he says. “It’s miraculous and it was the best experience I could have asked for—but I realized I didn’t love surgery.”

Then on a sub-intern rotation in internal medicine at a Mayo Clinic in Florida, Tarabochia found the patient-focused, cohesive care he was looking for. “I asked people if this focus on care is consistent across all Mayo facilities and received a unanimous ‘yes.’”

Given his preference for smaller, intimate environments, he surprisingly fell in love with the Mayo Clinic’s large internal medicine residency program where he found kinship among its like-minded residents. “I realized that I love big programs,” he laughs. “I want more people around me because that means there are more opportunities to learn—which is what I value in Mayo’s culture of education.”

But on a personal level, Tarabochia prefers a smaller scale. At Geisel, he created a much-needed life separate from medical school. During his third year he moved in with a friend from Plainfield, NH, “Living there gave me a strong sense of community—I was accepted—and a home in a small town that’s really cool. When I walked my friend’s dog, people stopped to chat with ‘the medical student’—it was a good life and I will miss it tremendously.”

Tarabochia’s fond memories extend to his medical education, too. “This school is clinically excellent. The providers in the community and the teaching sites beyond Hanover are excellent,” he says. “I don’t know how else to say it. I still have a lot learning ahead—but the way clinicians at Geisel interact with students, the questions I can ask, and the comfort I felt in most clinical situations was incredible.

“As a first-generation student I’ve worked hard to get myself here. And I feel really good about that, but I also know there are many, many equally qualified students who could have taken my spot. I can’t convey how thankful I am to be here—finishing and knowing I can do this has been transformative. I’m leaving here thinking I may return.”

Lye-Yeng Wong ’19: The Future Face of Surgery

Medical school can be full of surprises. First-year students often sure of what they want to pursue, change their mind once rotations begin. Though this isn’t true for everyone, it was true for Lye-Yeng Wong ’19.

“I fell in love with surgery during my third year, which was surprising for me even though many of my classmates said that choice was obvious from the start—the first day I dissected the cadaver,” Wong recalls.

Originally, she intended to practice emergency medicine, a decision she partially credits to her mentors prior to medical school. She found the field exciting, especially the fact that emergency physicians are generalists who need to be good at a bit of everything. “But now,” she says, “I want to be a specialist in one thing.”

Wong credits her involvement with Geisel’s chapter of Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) for turning her attention from emergency medicine—she got her first glimpse of surgery when she traveled to Nicaragua under the mentorship of a Dartmouth ENT surgeon. And between her third- and fourth-year of medical school, she participated in a research fellowship in Cape Town, South Africa, where along with conducting research—looking at heart failure in HIV patients—she worked shifts in the clinic’s emergency department. It was there that she was drawn to taking care of patients with penetrating traumas, such as stab wounds, who required stitches.

Back at Geisel, after four sub-internships in a row, including thoracic surgery and oncology at Dartmouth-Hitchcock, one in Seattle and another in Oregon, Wong was smitten. She fell in love with the program at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, which is where she’ll be doing her residency.

“By then, I was convinced I wanted to be a surgeon,” she says. “Surgery is a serious specialty that requires a lot of focused attention, thought, and skill, and I like that. I also like how you can significantly change someone’s life—one surgery can turn a life around.”

She feels equipped to handle the demands of the profession because of a lifetime in ballet. “I’m used to training hard—practicing moves over and over in order to perform during a period of high stress. That’s analogous to surgery and it’s why I enjoy that environment. Plus, I’ve always enjoyed hobbies that require eye-hand coordination—woodworking, ceramics, knitting.”

While on the residency interview trail, Wong overhead a fellow applicant talking about the dearth of female role models in surgery and how she wished there were more. Surgery, Wong notes, has always been an ‘old boys club’ where you have to ignore everything else in your life, but that’s changing.

“I’m really excited about going into a field where I can be part of that change. The lack of female mentors is something I’ve never even thought about, because they are abundant here,” she says. “Dartmouth is a good example of the future face of surgery.”