All research is rooted in a simple question about something specific. For Allan Munck, that question was: Where do glucocorticoids act? Spurred by intellectual curiosity when he set out to understand how glucocorticoids worked, he didn’t anticipate answering that question would be the beginning of a prolific career spanning more than five decades.

The central function of glucocorticoids is to protect against stress—they bind to receptors present in nearly every cell in our bodies and play a key role in regulating the immune system.

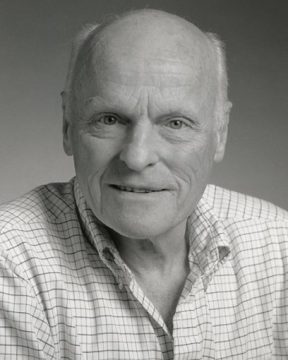

A world-renown researcher in the field of endocrinology, and considered by many to be the father of glucocorticoid receptors, which he discovered in the 1960s, Allan U. Munck, PhD, an active emeritus professor of physiology and neurobiology at the Geisel School of Medicine died unexpectedly on April 29. He was 90 years old.

Known for his “intellectual honesty, collegiality, and thoughtful mentoring,” Munck was a remarkable man who left an incredible and indelible legacy here at Dartmouth, says Duane Compton, interim dean.

Upon his retirement in 2000, Geisel (Dartmouth Medical School at the time) hosted a symposium, “Glucocorticoids and Beyond” honoring Munck for his contributions to the field, and established a lectureship in his name. More recently, with his blessing, Munck’s legacy will continue to live on through the Annual Munck-Pfefferkorn Prize Lecture. This fall, the inaugural Munck-Pfefferkorn Lecture will be delivered by Nobel Laureate Thomas C. Südhof, a neuroscientist known for his work in synaptic transmission.

Donald Bartlett Jr., MD, active emeritus professor of physiology and neurobiology at Geisel says of his former colleague and professor, “I met Allan as a first-year medical student—it was his first year on the faculty and he taught the entire endocrinology section of the physiology course. It was only toward the end of the year that we learned he had never taken an endocrinology course, and apart from the steroid hormones, he learned most of the material a few days before we did.

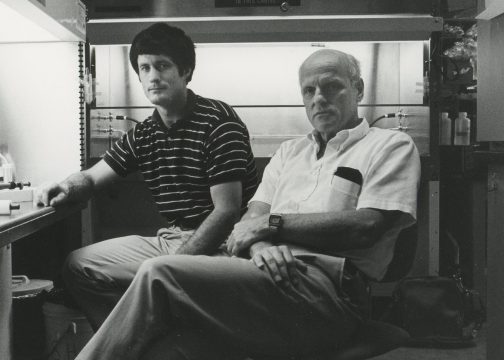

“At that time, the course included student research projects, and for several afternoons, two classmates and I worked under Allan’s supervision in his ‘laboratory’—the second floor hall in the old Medical North building on College Street,” Bartlett recalls. “Despite the primitive conditions, working closely with Allan was a great privilege, and I enjoyed it so much I later spent a summer in his real laboratory in the new Remsen building. Allan was an enthusiastic and friendly mentor and colleague, who could almost always think of a sound experimental way to determine how a biological system worked. I will miss his intellect and his good will.”

Charles Wira, PhD, a professor of physiology and neurobiology, had been friends with Munck for more than 50 years; they met in 1965 when Wira entered the PhD program at Dartmouth. “Despite the fact that I had no plan to do my PhD thesis research with him, I selected Allan as my advisor—it was one of the best decisions of my life,” he says.

“He guided, directed, and allowed me to make mistakes, many mistakes. Rather than telling me what to do, he suggested. This path took longer, but provided each of his students the opportunity to grow as independent scientists. He was an excellent teacher capable of explaining complex processes that all could understand.”

Kind, gentle, and supportive of all of those he came in contact with, Wira says Munck respected other people’s ideas, religions, and political perspectives. “Conversations knew no bounds, and right up until his death he was a true student and scholar,” Wira fondly recalls. “His excitement about finally being able to dig in and understand most of Einstein’s Theory of Relativity brought excitement to those of us with whom he shared his latest insights.”

Among Munck’s longtime physiology and neurobiology colleagues who portray him as a wonderful mentor and imaginative scientist, Aniko Fejes-Toth, MD, considers herself lucky to be amid the scientists who “grew up” in his lab.

“I was working in Hungary when I met Allan in the late 1970s at a scientific symposium,” Fejes-Toth recalls. “Later, in 1982, he invited me to join his lab as a visiting scientist.” An invitation that changed her life she says, “My husband and I came to Dartmouth for one year and stayed forever.

“Allan’s scientific integrity was unparalleled,” Fejes-Toth says. “For example, one day he received a handwritten letter congratulating his work from a retired scientist in the Netherlands who explained that he himself had raised a similar hypothesis many years earlier, which was published in an obscure Dutch journal. Allan had not seen the journal article, but from that point on, he always mentioned Dr. Tausk in reviews and scientific talks.”

Paul M. Guyre, PhD, professor of physiology and neurobiology and of microbiology and immunology notes receiving condolences from luminaries in the field remarking on Munck’s contributions to endocrine physiology, his mentorship, and his accessibility. “While I feel a terrible sense of personal loss,” Guyre says, “I also feel a tremendous sense of privilege and gratitude for decades of his outstanding advice and personal friendship.”

When Val Galton’s husband accepted a position in the Pathology Department in 1960, he did so with an understanding that his wife would also be accommodated. Galton, now a professor of physiology and neurobiology, recalls paying a visit to Munck in his lab in the old Medical North building on College Street where she was impressed with both his work and his enthusiasm.

“We both taught endocrinology,” Galton says. “At that time, Allan was not a morning person, so by mutual agreement I took the 8:00 a.m. lectures, while he took the ones in late morning and early afternoon. There were only 24 medical students then, so he created a project that paired students with an endocrine disease and charged them with developing a presentation—the students loved it because it allowed them to interact with physicians. This is just one example of his creativity and his interest in novel ways of teaching.”

During the 54 years that Galton had known Munck, she says he had consistently been there for her on both a scientific and personal level. He was always amiable, and above all kind to everyone.

“Despite how I try, my words seem shallow given the outstanding person Allan was and how he will remain in my memories,” Wira says. “He will be greatly missed for his intellect and his good will, and because many years ago he became a much-loved member of my family.”

A lifelong teacher and student with a voracious appetite for knowledge, Munck was well-known for his prolific and detailed note-taking, his delight in the wonderment of all things in the world, his love of deep conversation and analysis, and his boundless curiosity about what motivated people.

A lifelong teacher and student with a voracious appetite for knowledge, Munck was well-known for his prolific and detailed note-taking, his delight in the wonderment of all things in the world, his love of deep conversation and analysis, and his boundless curiosity about what motivated people.

Dedicated to fitness and health, Munck was an avid biker, runner, hiker, squash player, and skier. He could regularly be seen running on Hanover’s streets, wooded trails, or at Leverone field house up until his death. Also an accomplished cellist and connoisseur of classical music, Munck practiced daily and played in chamber groups twice weekly throughout his retirement. He leaves his wife, Claire, two children, and three grandchildren.

A celebration of Allan Munck’s life is being planned for later this summer.